The energy policies adopted during the current decade (1970s) will determine the range of social relationships a society will be able to enjoy by the year 2000.

Ivan Illich, 1974

Mapping the energy consumption since the 1970s indicates we chose a high consumption route with low social benefits. An equitable energy transition requires observation of overall consumption of our energy resources. Regardless of energy technologies, whether powered by fossil fuels or the sun’s rays, social inequality is dependent on society’s ability to ensure an equitable consumption of resources. Certain groups, whether divided by country, region or social strata, need to ensure an equitable range of consumption. Rather than seeing our natural resources as limitless, we need to perceive the consumption of these resource as finite as time. Even if these resources exist in the future, we threaten the viability of the future by over consuming our resources.

Framing our present climate crisis, we can consider society borrowed against the future of the environment and society. We are now stuck in a downward spiral dealing with the effects of climate change due to the overconsumption of fossil fuels. Another view from the 1970s is provided by Kurt Vonnegut in his book Jailbird, which is when the main character recounts the story of the tragedy of how life ended on another planet.

But they ran out of time on Vicuna, he says. The tragedy of the planet was that its scientists found ways to extract time from topsoil and the oceans and the atmosphere – to heat their homes and power their speedboats and fertilize their crops with it; to eat it; to make cloches out of it; and so on. They served time at every meal, fed it to household pets, just to demonstrate how rich and clever they were. They allowed great gobbets of it to putrefy to oblivion in their overflowing garbage cans.

“On Vicuna,” says the judge, “we lived as though there were no tomorrow”

.…But by the time he was fifty, only a few weeks of future remained. Great rips of reality were appearing everywhere.

Kurt Vonnegut, Jailbird. 1979, p 100

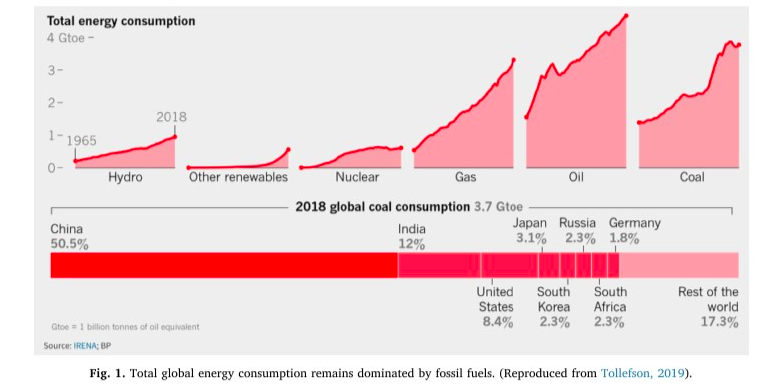

Looking back over the past 50 years provides us with a clear picture of the choice humans took. They burnt the fossil fuels to speed up economic development and live like there was no tomorrow. It was the pursuit of fast economic development with an understanding that this type of energy consumption was lifting millions out of poverty. The perspective of the past fifty years can be seen in the total energy consumption in Figure 1, China, India and many other developing countries rely on fossil fuels to create economic growth and improve society. Through this narrative it seems governments did not have a choice but to build a fossil fuel energy system. Looking at the choices made it is only recently that renewables begin to tick upward while only coal begins to level off.

The scientists have found more and more efficient ways to extract fossil fuels from the Earth. Most recently, this is in the form of shale gas using hydraulic fracturing technologies to create fissures of natural gas and oil. This technique ensures lower economic costs and a perpetuation of fossil fuels as the main driver for many national economies. The United States switched from being an oil and gas importer to exporter because of this technology. The prosperity of countries and society is dependent on these fossil fuels and the business of science behind it. The fossil fuel economy moves ahead regardless of the impact on future generations. Just like on the planet Vicuna, we live as there is no tomorrow and only now we begin to see the rips of reality in the form of disappearing icecaps, desertification, and firestorms consuming towns.

Human Development and our Energy Footprint

The Jesuit priest, Ivan Illich outlined the choices we had in the 1970s. He laid out two scenarios for society to take which would determine how we live in the year 2000. Similar to the projections of the International Energy Agency (IEA), he provides a ‘low energy policy’ which allows for a wide choice of lifestyles and cultures. The second scenario is a ‘high energy consumption’ where social relations are “dictated by technocracy and will be equally distasteful whether labelled capitalist or socialist.”2

The low-energy policy ascribes to a rationed approach to energy consumption with an upper national limit, thereby ensuring greater energy efficiency and a higher level of equity for society. The upper echelons of society must also limit energy use just as the lower (or even 90%) portion of society limits their energy consumption due to cost. Social well-being is connected to per capita energy use. However, for a low energy route, there needs to be a limited use by elites of their energy consumption, with resource management and a “thermodynamic thrift” for industry. Low energy consumption by all of society (and industry), according to Illich, produces a more equitable energy system

Looking back the world chose the high energy scenario in pursuit of economic and social development. No limits on consumption and behavior akin to the planet Vicuna where our use of oil-based plastics is akin to our overflowing garbage cans with plastic packaging and objects. Our present wealth derives from our scientific discoveries which opens up an equity gap where the seen route to economic and social prosperity is to also participate in the pursuit of consumer goods, rather than the pursuit of equity.

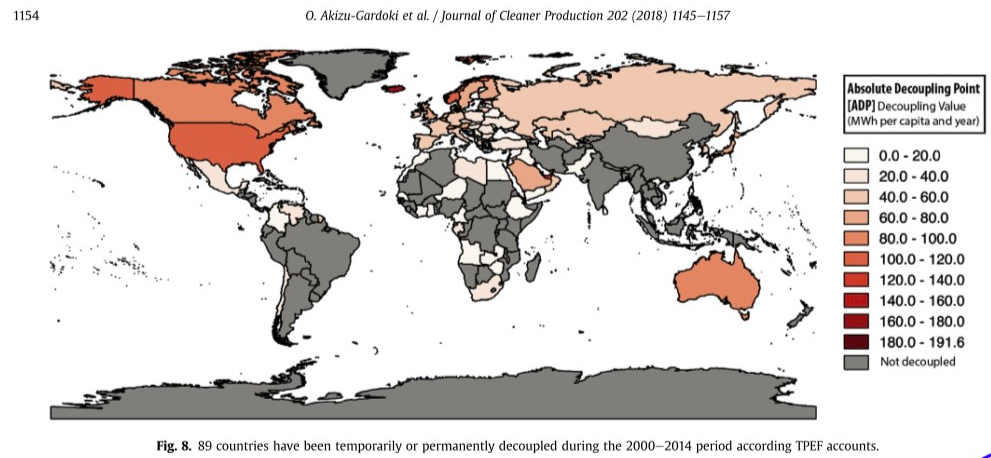

In 2000 Illich’s choice can be shown. The connection of economic growth to the use of energy can be seen as coupled with energy consumption and economic output. Represented by the connection between MWh of consumed energy compared to the Total Primary Energy Footprint (TPEF) of a country. Accounting for a country’s footprint is “a well-established method to trace the total resource needs and environmental impacts of a country’s consumption”3 In the below map we can see the degrees countries have and have not decoupled their economic growth from energy consumption.

The identification for the threshold for the energy footprint aligns with Illich’s identification of “the need for limits on the per capita use of energy must be theoretically recognized as a social imperative.”2 The disparity in the 1970s were identified by comparing the energy in transport. “250 million Americans allocate more fuel than is used by 1,300 million Chinese and Indians for all purposes.”2 The dramatic economic growth of China and India since the 1970s can be seen by the huge increase of energy production and consumption, so that by 2014 these countries economic growth were directly connected to their energy consumption. To economically grow the economies through a quick route required a tremendous scaling up of energy production to deliver economic growth for their societies. While the developed countries also pursued this route, they are now leveling off and decoupling this growth.

This macro perspective of the GDP to energy footprint ratio covers up the internal disparities between the elites of each country and the dipropionate consumption of energy. If in the 1970s, the disparity was observable at the macro perspective between countries, in the 2000s the internal disparities even in developing countries is observable. But so too are the huge transport networks in China and India observable for moving the population around at a quick pace. The impact of the choice made in the 1970s in the year 2000 is clear. The world chose the high energy scenario leaving huge inequalities at global and local scales. This inequality now spreads into the future for generations who must grapple with our overconsumption of fossil fuels like there was no tomorrow.

The tragedy for our Earth, reframing Vonnegut’s perspective of events on Vicuna, was the technological developments that resulted in the mining of time through fossil fuel extraction. There are two central ways to assess an equitable energy transition. Drawing from Sen, these central ethical issues for the analysis of equality are: “(1) Why equality? (2) Equality of what?” To date the representation in the above map indicates the spatial inequality of countries and who has and who is consuming unsustainable levels of fossil fuels. The pursuit to decouple energy consumption from economic growth is perceived to be the pinnacle of a sustainable energy system. The goals of 2050 to be ‘carbon neutral’ are held up by politicians, scientists and the believers in climate change as a means to save our Earth. This argument answers Sen’s first question, ‘why equality?’ This question was important in the 1970s when we could have chosen a low or high energy scenario. Fifty years later, this question is moot.

Equality of Time

The question now is, ‘Equality of what?’ Because for Sen, different perspectives lead to different views on equality “liberties, rights, utilities, incomes, resources, primary goods, need-fulfillments, etc.”4 Sen sets off his approach from the notion of a ‘utility function’ where the gain of liberty for someone is due to the loss of liberty for another. Nonetheless, through Illich’s interpretation and considering the one system’s approach of the Earth, there is a cap on natural resources and a limit to CO2 emissions from fossil fuels. The distinction is important, as there may not be a utilitarian limit to liberties and rights for people, but there is a limit to natural resource consumption. The technological methods may differ – consumed in a car, factory or power plant, but energy consumption is tied to the amount consumed in a period of time. The faster the consumption the faster the economic development, and in all countries – at some point in time – the closer we come to running out of time to retain a biodiverse ecosystem supporting life.

The discussion needs to shift from a spatially uneven development of Earth’s societies and resources – since the Earth is one system not restricted by fences and border guards. Now the question is one of uneven remaining time on this Earth. As the Climate Change cycle speeds up, floods, drought and temperature shifts, the spatially uneven process is not one of economic development but retention of habitable living areas. Coastal zones are reclaimed by the sea, forested areas burn while shifting temperatures zones alter how people live and influence whether they can stay in their homes.

The question in the 2020s is Equality of time, not equality of place. Like the creatures of Vicuna, we’ve ate, burned, polluted and drank our future away. There is always a future, but in fifty years we just consumed the future health of all beings on Earth. The hang-over from this era of over consumption is now upon us. Spatially inequality is marked by not only who has benefited the most from fossil fuel consumption, but which communities can stay intact and in-place.

Conclusion

Our global society lived like there is no tomorrow. The energy policies adopted since the 1970s, emphasizing fossil fuel use, were backed by powerful technological developments and political guidance to ensure economic development over sustainable development of the Earth’s resources. Inequality increased as countries and societies saw the rise of elites consuming unsustainable levels of energy and products. The social inequality we examine is not caused by the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy, but through the consumption of fossil fuels to power a hyper-environmentally unsustainable economic development. The energy system, including transport and manufacturing, is created to ensure higher income social groups are able to benefit from low energy prices and in turn low cost consumer goods trickling down in the form of used clothes, appliances and polluting second or third-hand cars. What we perceive as wealth in our garbage cans or recycling bins, of mountains of plastic and discarded food, is paid for by our common future.

As Vonnegut puts the nearing collapse of Vicuna, “.…But by the time he [the judge] was fifty, only a few weeks of future remained. Great rips of reality were appearing everywhere.”5 With these great rips of reality seen in our changing Earth from the extinction of species to melting polar ice caps, comes a more fundamental debate over the inequality of time rather than spatial inequality. We should not see we have thirty years to finally build an equitable energy system by eliminating CO2 emissions from fossil fuels. Rather we need to implement three key steps to repair the rips in time: First, repair the environmental damage over the past fifty years when we chose a high energy scenario. Second, we need to build a low-energy system that is equitable by reducing over consumption by the ‘haves’ and assist the ‘have nots,’ so all groups equally draw from the same resource budget, and not utilize the future’s resources. And finally, stop fooling ourselves that we can have a technological fix to our energy requirements. Social values and the value we place on environmental resources must change. Social inequality is not caused by a shortage of natural resources, but the distribution of these. Distribution relies on humans and their social institutions. The collapse of Vicuna was because they ate their time, it seems we’ve eaten ours.

References:

1Jenkins, Kirsten E.H., Benjamin K. Sovacool, Andrzej Błachowicz, and Adrián Lauer. “Politicising the Just Transition: Linking Global Climate Policy, Nationally Determined Contributions and Targeted Research Agendas.” Geoforum 115 (October 2020): 138–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.05.012.

2Illich, Ivan. Energy and Equity. Great Britain: Calder and Boyars Ltd., 1974.

3Akizu-Gardoki, Ortzi, Gorka Bueno, Thomas Wiedmann, Jose Manuel Lopez-Guede, Iñaki Arto, Patxi Hernandez, and Daniel Moran. “Decoupling between Human Development and Energy Consumption within Footprint Accounts.” Journal of Cleaner Production 202 (November 2018): 1145–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.235.

4Sen, Amartya. Inequality Reexamined. Oxford University Press, 1995. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198289286.001.0001.

5Vonnegut, Kurt. Jailbird. The Dial Press, 1979.

Dr. Michael LaBelle is an associate professor at Central European University in the Department of Environmental Sciences. He produces the My Energy 2050 podcast to change how we communicate and improve the energy transition.

Well explained.